by Bill Bonner – Bonner and Partners.com:

The key feature of age is that it happens no matter what you think.

What does this mean?

It means the “old countries” – their assets and their institutions, at least the ones that depend on population, income and credit growth – are “fastened to a dying animal” and are not likely to survive in their present form.

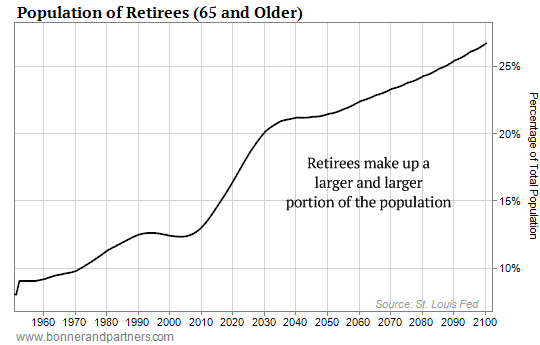

Today, these countries, including the US, are victims of demography. Older people get more money from the government. And they pay less in taxes. Old people also slow the rate of GDP, for obvious reasons: They are not adding to output; they are living on it.

As people age, the whole society – its institutions, its laws, its customs, its economy and its markets – ages, too. They all become as familiar, comfortable and shabby as a well-worn shoe.

An economy is not independent of the people in it. The economy ages with them. And when they reach retirement age, the economy gets arthritis.

A Nursing Home Economy

Even the Congressional Budget Office has noticed how government debt slows growth:

Increased borrowing by the federal government generally draws money away from (that is, crowds out) private investment in productive capital in the long term because the portion of people’s savings used to buy government securities is not available to finance private investment.

The result is a smaller stock of capital and lower output in the long term than would otherwise be the case all else held equal (CBO, July 2014, p. 72).

Why does the federal government need to borrow so much? Before the invention of the welfare state, almost all large borrowing was done for war. Since the end of World War II, however, most developed countries – with the exception of the US – have borrowed heavily only to pay for social programs.

But neither debt nor spending contributes to a dynamic, innovative and growth-oriented economy. Instead, they produce an economy that looks like the people in it – old, creaky and in need of around-the-clock care.

As people age, they begin fewer new businesses. “The Other Aging of America: The Increasing Dominance of Older Firms” is the title of a major study from the Brookings Institution. Done by Robert Litan and Ian Hathaway, it showed that American business was becoming “old and fat.”

Taken together, the data presented here clearly show a private sector where economic activity is sharply concentrating in older firms – a trend that is occurring in a nearly universal fashion across sectors, firm sizes and geographies…

An economy that is saturated with older firms is one that is likely to be less flexible, and potentially less productive and less innovative, than an economy with a higher percentage of new and young firms.

Young people try to create new wealth. Old people try to hold on to the wealth they believe they have in the bag. They are less entrepreneurial. They are also, perhaps, more eager to protect their businesses and professions from competition.

Part of the reason for fewer business start-ups is that it has gotten a lot harder to launch a new company in America.

That was the conclusion of a study by John W. Dawson and John J. Seater (“Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth”). What they found was that there has been a huge increase in economic regulation and restrictions in the US since World War II. They point out that these regulations have an economic cost. Like debt and demography, regulations reduce output.

In fact, they estimate that had the level of regulation remained unchanged since the year I was born – 1948 – today’s GDP would provide every man, woman and child in America with about $125,000 more in income per year.

A Glorified Ponzi Scheme

It was Alexis de Tocqueville who observed that democracy was doomed. He said it would soon degrade into tyranny. As soon as politicians realized that they could win elections by promising the voters more of other people’s money, it was just a matter of time until they overdid it.

Had he imagined how old people would get, he wouldn’t have been so optimistic.

As things developed, politicians noticed two important things: that young people (especially those who hadn’t been born yet) didn’t vote… and old people’s votes could be bought fairly cheaply, at least so it appeared at first.

When the US Social Security program was first put in place, for example, the typical American male could expect nothing from it. He was expected to live to 61. He’d be dead before benefits kicked in. But as the 20th century led to the 21st, his life expectancy increased, and so did the burden of old people.

Early Social Security participants paid in trivial amounts and got a very good return on their money. My mother, for example, only worked a few years at a low-paying job, from which she retired in 1986. She has been collecting Social Security ever since.

“Don’t you feel guilty about getting so much more than you put in?” I teased her.

“Not at all. That’s just the way the system works.”

The way the system works would be illegal for a private annuity plan. It would be labeled a Ponzi scheme. Its promoters would be fined or put in prison. The money that goes into the system is not locked away in wealth-producing investments so that the cash will be available to finance the retiree’s pension. Instead, the contributions of new participants are used to pay benefits to old ones.

This has the obvious and fatal flaw of all Ponzi schemes – eventually, there is not enough new money coming into the system to meet its obligations. This point was reached in the US system in 2010. Since then, the system has been running an annual deficit.

You’ll see why in the chart showing the retirement-age population.

Everybody knows Social Security, the Affordable Care Act, veterans’ pensions and other support programs are dangerously underfunded. What is not appreciated is the effect that this has on GDP growth and stock market prices.

The crankshaft of age leads to the universal joint of social spending, which then goes to the axles of debt. Finally, where the rubber meets the road, the wheels turn more slowly.

This is not just a problem for government finance. Companies make money by putting out products and selling them. But when people grow old or population growth declines, so do both supply and demand.

Then, companies earn less money. Their shares are worth less. Personal incomes go down. Capital gains retreat. And tax revenues fall, too.

When this happens in an economy that is already deeply in debt, it triggers a crisis.

Article originally posted at Bonnerandpartners.com.